Britain's growth problem isn't a mystery

An unsure government leads to a stifling of capital injected into businesses. Strong leadership allows for entrepreneurs and investors to plan, and it's what the UK desperately needs in order to grow.

The British economy has spent the past year as listless as a housecat: mostly sprawled across the sofa, occasionally stretching just enough to remind you it’s still alive. Growth, that essential to balancing interests and satisfying demands, is struggling to get out of first gear. That’s not an accident, it’s the result of decades of poor choices followed by a year of uncertainty.

Two forces lie behind this stagnation: the short-term chaos of regulatory volatility, and the long- term capital starvation engineered by decades of pension rules. One makes businesses hesitate today; the other leaves them unable to invest for tomorrow. Together they form the architecture of the economy’s current malaise.

We should be led by a confident administration offering predictability and a steady easing of burdens. Instead we face confusion. Ministerial briefings followed almost immediately by denials have left businesses unsure how to respond. Firms can cope with high taxes, irritating regulations, even bureaucratic absurdity, but they cannot cope with constant change. Britain has made volatility a national sport, with Labour its Olympic champions.

National Insurance, the tax on earned income, has yoyoed in recent years as governments, including Conservative ones, tried to appear dynamic rather than strategic. Labour’s long-trailed Employment Bill has lurched in and out of view, raising fears of heavier burdens on employers. And the run-up to Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s Budget has been the most erratic yet: rolling pitch after pitch of for tax changes that ended up as own goals.

Small employers feel this most keenly. Four in five businesses have fewer than ten workers, and any last-minute rule change can be catastrophic, so hiring and innovation are delayed until government settles on a direction. Energy regulation shifts with every new ministerial whim, offering an extravaganza of targets, caps, floors, carrots, sticks and exemptions. Trade rules and import paperwork continue to mutate post-Brexit. Even pensions, allowances and capital treatment, once stable fixtures, now lack predictability.

Uncertainty breeds hesitation. A firm that might have expanded instead waits. A family that might have moved jobs pauses. Entrepreneurs delay. Investors reconsider. Consumers save. The economy slows, then creaks, then stalls. Regulatory volatility has knocked the economy off balance in the short term.

Investment in the last quarter was pretty much flat, productivity is sulking, and business confidence has all the buoyancy of a wet sandbag, as the Office for National Statistics confirms.

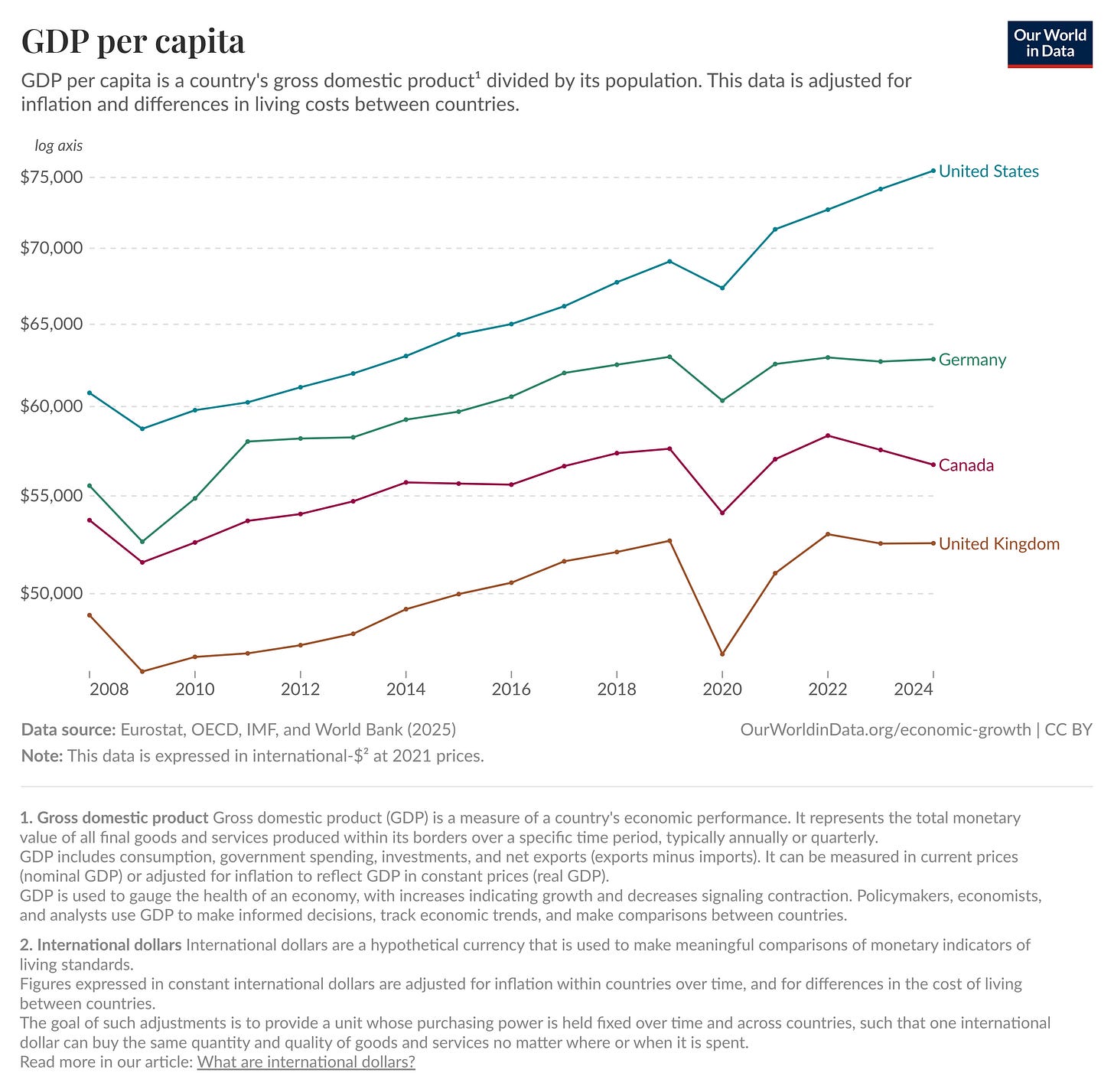

The result is obvious: the UK has not grown. Per capita, we are up 4 percent since the global financial crisis; Canada is up 22 percent, and the US 79.

But another, deeper force has been draining its strength for decades.

In the aftermath of two major pensions scandals in the 1990s, regulation swung sharply towards caution. Capital that once flowed into businesses, live money funding innovation, expansion and hiring, came to be treated as excessively risky. Regulators pushed pension schemes and insurers towards bonds, which promised safety but created little. Bonds don’t boost productivity or employ anyone; they simply track the economy rather than drive it, weakening the intergenerational contract that once channelled savings into future growth.

What was intended as prudence became, over time, a slow siphoning of the economy’s lifeblood. The ONS has become the country’s nurse, taking the nation’s pulse and finding only a thin, faltering beat, the signature rhythm of an economy starved of capital.

The past year merely continues this long decline. Business investment is barely crawling on an annual basis and shrinking quarter-on-quarter. Productivity has risen by only half a percent since 2010, roughly half that of Germany or Canada. Whatever the Treasury insists, this is not the profile of an economy preparing to grow.

Government points to rising tax receipts as evidence of success, but in a low-growth economy this is a hollow triumph. High receipts can signal over-taxation and fiscal drag, a doom loop in which tighter control suppresses the very growth that would otherwise expand the tax base. Meanwhile, with the state spending around 45 percent of national income, the private sector has even less room to manoeuvre. A tax system that should encourage dynamism has become a cumbersome tollgate, one whose charges shift unpredictably.

Businesses need the space to take risks, to succeed, to fail, and to try again; but with a drunken sailor holding the tiller, no one has secure footing. Risk is multiplied, and the natural dynamism of the economy collapses into stasis. Put these forces together and the past year looks inevitable rather than mysterious. Investment is too low; regulation too volatile; taxes too fiddly and too frequently adjusted. Ministers announce, adjust, tinker and retreat. Entrepreneurs hesitate. Firms delay. Consumers worry. Productivity crawls. Growth flat-lines.

None of this is necessary. Britain has talent, capital and ambition. Combined, they could transform our economy and empower our friends abroad. But they require something essential that Britain has not recently had: stability and long-term capital. Growth is the sum of millions of individual decisions to invest, hire, expand, save, spend, and innovate. Those decisions require confidence. Confidence requires stability. And stability requires a government that understands the value of staying still and allowing capital to grow.

Until that happens, Britain will remain where it is now: waiting for growth, hoping for the best, and wondering why the future keeps refusing to arrive.

This problem of uncertain is exacerbated by the longer term inability to control the public finances. We know that various forms of welfare, social care, the defence bill and the NHS will creep up, yet as of yet have been unwilling to either raise taxes or make the hard choice and decide what has to get frozen or cut. Where we do make cuts, it is often to the bone and muscle of the state (justice and prisons being a recent standout example), whilst the largest items of spending continue growing.

The effect of this is that whilst business may get a tiny sugar rush from short term handouts in the budget, they know that long term financial adjustment is inevitable. Until you deliver a budget that makes long term sense, business will lack any confidence to invest.

The FT have deep dived the biggest lever for growth: reverse Brexit; major planning deregulation; build baby build; cheap nuclear energy;