Can government deliver without AI?

Complexity and global comparisons mean that China's infrastructure porn is leaving the rest of looking naked. Government legitimacy comes from competence not only constitutions, we need AI to deliver.

One of my annual rituals is conducting a school bus survey. At the start of each year I try to help kids around the county who have been left on the side of the road by overfilled buses or others not showing up at all, to get to school. For some reason, despite knowing which school they’re going to and where they live, no one has connected the dots so more than a thousand families take time to tell me which routes their children take every day.

That should be easy to fix. After all, the data is all available to the county council, the bus routes are licenced by them and the schools don’t move. But somehow it is all too complicated.

That’s true with other problems. We have the logs of dropped calls and dead spots for mobile data, but is it the mobile phone operator or the government responsible for coverage? We know the impact of disruption, and worse, on communities by problem individuals, but is it the police or the council the lead for anti-social behaviour?

Again and again the question is not whether we knew but what did we do with the information and who was in charge of fixing it. Too often the answers are: nothing and no one.

This isn’t just a complaint about the bureaucratic wiring of the state but the right to govern.

It isn’t democracy alone that grants authority, but the ability to deliver and fix the problems our people face. Political legitimacy once flowed from constitutions, elections, procedures. Today, it flows from whether bins get collected, trains run, phones connect, children reach school. This represents a shift from procedural to performance as a government’s defining test.

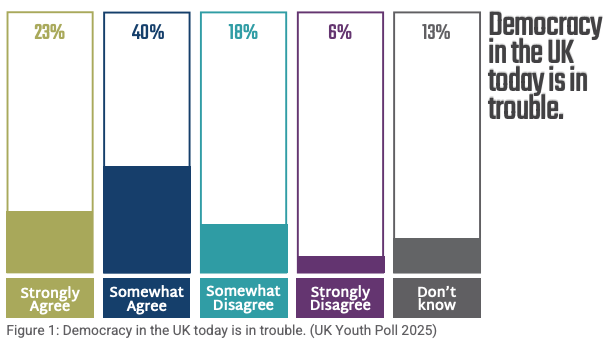

And we’re failing. Sixty-three per cent of young Britons believe democracy is “in trouble.” More than half think representatives don’t care about them. This isn’t mere frustration, it’s active delegitimisation.

The contrast is stark. You can watch Chinese infrastructure porn on social media: high-speed rail lines built in years not decades, massive solar farms going up in months, cities put up seemingly overnight. Then look here at home: HS2 cancelled, potholes multiplying, planning taking years, mobile signals failing everywhere.

My casework tells the story: not revolutionary anger, but something more corrosive. Citizens reduced to begging their MP for services they should be able to rely on and legitimacy dying by a thousand small failures.

Many MPs see the same as people turn to them in an attempt to solve these problems but the truth is, that’s only a sticking plaster, and each year, it gets harder.

Increasing complexity is punishing bureaucratic systems designed for a simpler age, and we can’t just spend to fix it. We have run out of money, now we have to think.

That’s where technology comes in.

In a headline-grabbing gimmick, Albania has appointed an AI bot as a government minister. That’s not a real solution. Human oversight, the mandate of an election and the continued accountability of those in power to people not algorithms must be at the heart of governance. But there is more we can do.

Accountability to people not algorithms must be at the heart of governance

Augmenting intelligence, making people more productive and able to see through the complexity to deliver results more quickly and efficiently should change how we think about government. We can move away from the state as controller to the state as coordinator, feeding data sets from different sources together so that companies and agencies can interrogate them to improve their delivery.

That should help reduce the current tax burden which is such a weight on individuals that it is punishing growth.

This is about more than delivery. Without artificial intelligence, democracies will struggle, because something fundamental has changed and the competition we’re in with autocracies makes it stark.

For decades we were the model: free markets, democracy, rule of law. China’s success shattered that monopoly. The question has shifted from “Will China democratise?” to something harder: “Can democracies deliver?”

When Britain demonstrated superior firepower that Chinese scholars couldn’t explain from Confucian principles, their civilisation was destabilised until their inherited beliefs slipped into alignment with observable reality. The gap between tradition and reality has created our own crisis today.

We have a choice: are we going to face reality and do better?

Some are trying to copy the authoritarian regimes by embracing industrial policies resembling state capitalism while insisting they defend free-market principles. History suggests such selective borrowing rarely works as architects imagine.

Even in Britain, some are suggesting returning to the nationalisation programmes we tried in the 60s that led to the economic collapse and the three-day week in the 1970s. That’s not the answer. Instead, we have the chance to embrace technological transformation enabling delivery at scale.

This isn’t just about democracy at home but alliances abroad. We are being weighed in the balance and found wanting.

We are being weighed in the balance and found wanting. We are being compared with China where infrastructure porn is contrasted on social media with delays and potholes at home.

That’s why AI matters so much to Britain.

It’s not magic. It requires massive infrastructure investment, workforce retraining, new governance frameworks, and constant vigilance against bias, but it’s the only path avoiding either unsustainable tax increases or steadily degrading services.

Twenty-first century democracies that survive will marry their procedural strengths-accountability, transparency, responsiveness-with actual capacity to deliver. Augmenting every civil servant. Automating coordination. Making data-driven real-time decisions. Using AI to close the gap between complexity and human capacity.

Trains must run, buses connect, phones have signal. To put it simply: things just have to work and my annual survey should become unnecessary because AI-augmented systems have spotted the patterns that have fixed the problem before it happened.

This isn’t authoritarianism. It’s the mathematics of democratic survival in an age of overwhelming complexity.

Governments that fail this basic test will face a tougher question: Why should we keep you?

Thank you, Mr Tugendhat. I did enjoy this. I broadly agree with you. AI has the potential for so much in our United Kingdom, and we already have one of the strongest bases in relation to most countries (I hear we are third in the world when it comes to AI, behind the US and China). So I am bullish. But I am weary that it will actually become reality. My fingers are crossed, but it feels as if a fair bit of possibly transformative government technology projects, for the most part, stay as concepts or fail. Of course, maybe we just need to "suck it up" and plan for the long term, where we treat AI like HS2 (before the two northern legs were scrapped), probably a pain to implement and awfully expensive, but could really transform governance and stop the dredge of just things failing to function.

Take a look at the Tony Blair Institute, they’ve been (rightly) banging this drum for a while