Guarding the seabed

With so much traffic and trade now moving unnoticed on cables on the seabed, mapping and sabotage of our maritime networks is leaving us vulnerable to systems go dark.

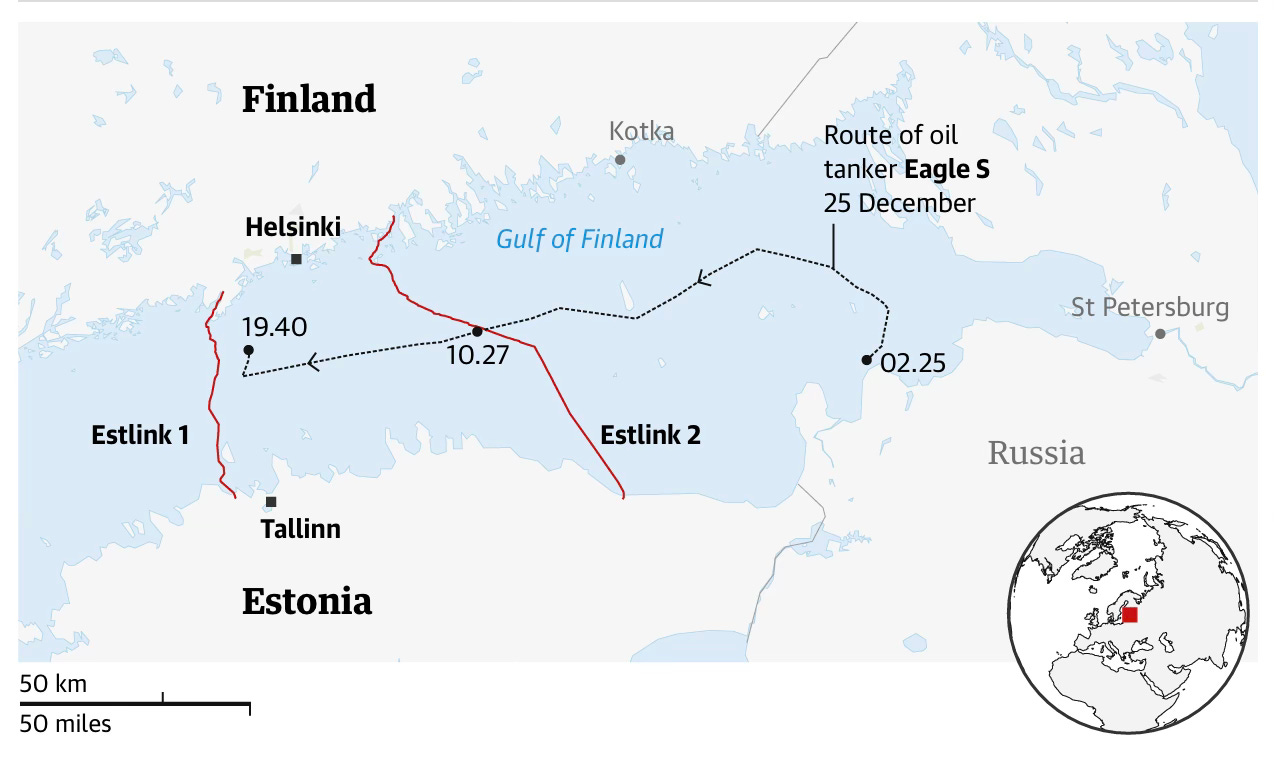

Last Christmas, Finnish authorities boarded and detained the oil tanker Eagle S in the Baltic Sea. The Estlink 2 undersea power cable linking Finland and Estonia was cut and other telecommunication cables damaged. The vessel, registered to the Cook Islands and suspected of being part of Russia’s shadow fleet, had dragged its anchor across the seabed, severing the link.

Whilst no shots were fired, the attack on two NATO states had cost millions and silenced trade. That wasn’t the first time we have seen how exposed the sea has become. From the Russian spy vessel Yantar just outside the UK’s area of the North Sea, to the numerous warships in Irish waters, mapping and sabotage of our maritime networks is growing. With so much traffic and trade now moving unnoticed on cables on the seabed, this is a vulnerability that could see many systems go dark.

These slow, ambiguous, and, some would claim, plausibly accidental attacks are increasingly how pressure is applied at sea, particularly in the Baltic and North Atlantic. Moscow and Beijing are exploiting our and our allies’ reticence to act militarily and instead turn to legal and administrative answers. That cannot last, it is already threatening our future.

So the question must now be: how do we shift the dial to deliver effective deterrence to these bullies? What tools do we need in our arsenals to allow states to see, record, and attribute this behaviour early enough to deter it, and if needed, to intervene? What kit can we have which allows interchangeability with our allies so that we can respond together more impactfully than alone?

The problem this maritime coercion exposes is not just about intent, but also our capability to respond. Most navies are built to fight battles, not to provide persistent awareness across the surface, air, and seabed in what remains legally a peacetime, but is now a competitive environment. The demands on manpower and endurance are high and difficult to maintain. That’s why technology is increasingly seen as the answer.

Uncrewed systems allow persistent aerial surveillance, surface monitoring of commercial traffic, and underwater inspection of cables and pipelines better than traditional crewed ships, but these systems do not operate alone. They require power, command and control, maintenance, data fusion, and legal authority. That shifts attention to the ships that support them.

Today, there is growing demand for ships that can sustain that presence across allies: a surface combatant with space and flexibility, endurance, and the ability to integrate unmanned platforms across multiple domains. The UK’s Type 31 frigate is the Royal Navy’s choice. Prioritising flexibility, modularity, and integration over specialised, single roles is the capability requirement of allied fleets.

These ships function less as fixed weapons platforms and more as hubs: as bases for aerial drones extending surveillance range, surface drones tracking or shadowing vessels of interest, and underwater vehicles inspecting seabed infrastructure. Their primary contribution is not firepower, though they have that too, but coherence: turning many distributed sensors into a shared operational picture that can be used by multiple nations simultaneously.

That is particularly important for the Joint Expeditionary Force, which operates in the Baltic Sea where incidents like the Estlink 2 damage occur: crowded, shallow seas with dense infrastructure and constant probing activity that rarely crosses the threshold of attack but is clearly hostile. In this environment, escalation control matters, and that requires persistent observation, clear attribution, and the ability to coordinate across countries. Combat power alone won’t help.

When a suspicious vessel damages a cable, speed is vital. The value of the navy lies in already having data from underwater inspections, surface tracking, and aerial surveillance, collected and shared across allied systems, allowing immediate action. Speed acts as a deterrent, not just an enforcement. That demands common standards, shared architectures, and platforms designed from the outset to host allied equipment.

This is where modular design becomes strategically important. A vessel that can embark different nations’ drones, sensors, or command modules without bespoke integration enables genuine burden sharing. One ally may specialise in underwater systems, another in aerial ISR, another in data processing or legal attribution. The ship itself provides the connective tissue. For the Royal Navy, the Poles, and the Indonesians, the choice is the Arrowhead 140, known as Type 31 in the UK, being built in the Rosyth shipyard in Scotland.

The Royal Navy’s Type 31 is a platform for unmanned maritime defence. Sharing the standard would enable interoperability and greater cooperation enabling oversight and deterrence.

As other Nordic states consider their next steps, building on existing maritime capability to protect their seas and shallow waters deepens the existing strength of others and extends the network. The UK and Norway’s maritime sensors and autonomous systems are most valuable when they can be combined with power-plants and others’ extensive new capabilities. Shared platforms, with a shared approach to design, allow those strengths to reinforce one another.

Last year’s Christmas present was the warning that we cannot continue responding to challenges; we have to get ahead of them. This isn’t achieved through single-vessel or single-navy choices alone, but through meeting the realities of present-day maritime competition unfolding in our waters and building 21st-century fleets structured to get ahead of it.

As threats to our economic security focus on the seabed and the grey zone, the most valuable ships we can invest in are those that integrate, connect, and persist, rather than those that simply carry the most weapons, and the choices of our allies will affect our own protection. The Baltic is not a foreign sea, and the connections to Ireland matter to us all.

Russia has shown it is serious, so the question is: are we?

Solid piece on the modular approach to maritime security. The shift from single-purpose warships to platforms that integrate distributed sensors and unmanned systems really does change deterrence calculus. I've seen similar thinking in how sattelite networks get designed, where resiliance comes from redundancy and flexible coordination rather than any single hardpoint. The speed-to-attribution point is key.

Interesting perspectives on the subject, thank you for sharing your thoughts. What do you make of the new 'Atlantic Bastion' mission, unveiled last week by the MoD?

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-unveils-new-undersea-warfare-technology-to-counter-threat-from-russia