How did we get here?

If Britain wants influence, it must start by making itself indispensable

The US response to Russia’s negotiations misunderstands the reality of the threat. They are not alone. From Washington, the dispute looks like a land deal. From Europe it looks like a problem for the east. The truth is more fundamental, for both of us.

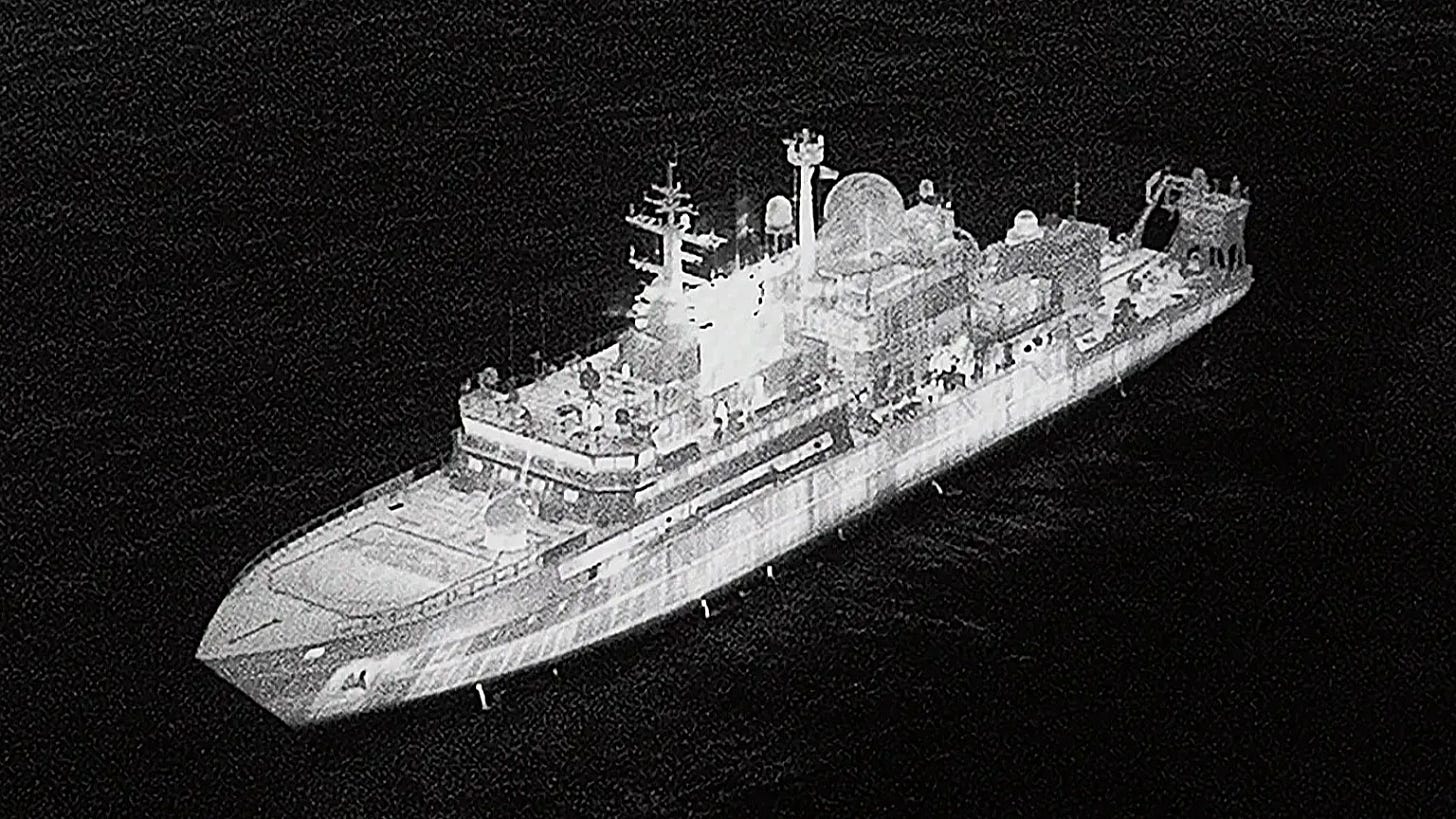

Russian intelligence ships have been mapping our waters for months. They search for undersea cables, energy pipelines and communication lines, probing the vulnerabilities we once assumed were secure. We are not alone in this. Across Europe, sabotage plots, assassinations, disinformation campaigns and industrial disruption have become routine features of a Russian intelligence strategy updated for the modern world but rooted in the habits of the KGB. This is the reality of strategic competition whether we acknowledge it or not.

The erosion of cohesion across Europe continues. The war in Ukraine has masked a deeper truth. Russia’s goals are not limited to territory. They are trying to corrupt the world we built. Yet our reply has been a promise to raise defence spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2030, a date placed safely beyond the next election, after today’s ministers have moved on and far too late to respond.

So what should we do?

The first step is to abandon the comforting illusion that strategy can be drafted in time with the spending cycle or delivered by press release. If we want to defend this country, we must fund the Armed Forces to carry out the strategy we ourselves published. That requires increasing defence spending now, not in a future parliament. It means restoring basic strength in personnel, logistics and stockpiles, expanding munitions production and rebuilding capabilities we have allowed to wither, from amphibious forces to air defence. Strategy without resources is theatre.

Second, we must put intelligence to work. Russia is showing how small investments can create far greater effects than traditional weapons. Ukraine is demonstrating how technology can level an unequal fight. Britain’s intelligence agencies remain among the finest in the world, capable not only of exposing threats but of imposing costs on adversaries. They require leadership that matches their ambition. Investment in offensive cyber, clandestine operations, technical intelligence and serious counter-interference is one of the most efficient ways to shift pressure back onto Moscow. We need a national plan to protect cables, grids, offshore wind, ports and data centres, and an equally determined plan to disrupt Russian networks abroad. Defence deters force. Intelligence deters intervention.

“Russia isn’t fighting for land - it’s attacking the systems that keep our world standing, while we comfort ourselves with promises for 2030.”

Third, we must help build a European industrial base that can sustain a conflict. The Libya campaign in 2011 exposed how fragile our capabilities were. Stocks that should have lasted months were counted in hours. Europe cannot deter an authoritarian state with peacetime production lines. Shared stockpiles, common standards and joint production of munitions, drones, air defence systems and long-range fires are essential. Britain should lead this effort. When Europe manufactures at scale, Britain gains freedom of action.

Finally, we must restore credibility with our allies, especially the United States. Influence follows contribution. If we want a voice in decisions about Ukraine, European security or the future of NATO, we must show we can carry our share of the burden. Complaints that Washington is not listening are not the words of a serious nation. Serious nations make themselves indispensable and difficult to ignore.

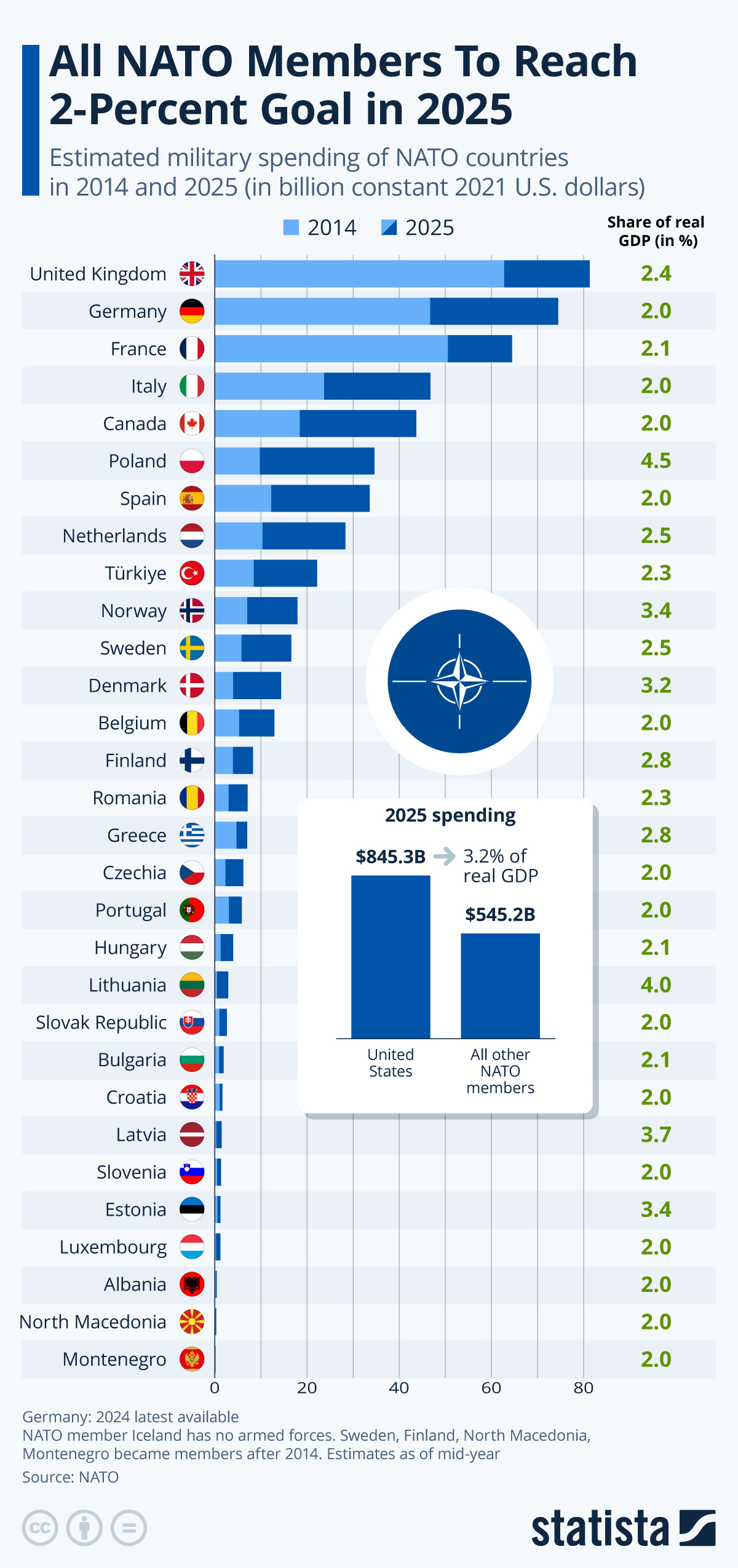

None of these steps are impossible. Europe is already moving. Poland has rebuilt its armed forces on a scale unimaginable a decade ago. Its government will spend 4.8 percent of GDP on defence next year, not in five years’ time. By the end of the decade it is projected to field more tanks than Germany, France, Britain and Italy combined. Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia, each with economies small enough to fit inside Greater London, spend more than 3 percent of their GDP on defence, have reintroduced conscription or strengthened reserve forces and openly discuss going further. Geography gives them no choice. They have become serious.

We have preferred distant targets and vague aspirations. Inside the Ministry of Defence reality is already pressing in. A 2.6 billion pound overspend has made the Strategic Defence Review impossible to deliver on current budgets. The service chiefs know this. In an extraordinary meeting they told ministers plainly that without more money and quickly, capability will fall. There is no middle course.

This pattern is not new. Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya each revealed the same flaw. Britain commits to operations it cannot sustain. We send troops without adequate equipment, run down stockpiles, delay procurement and convince ourselves that the wars we are fighting define the wars we will face. In Libya, confronting one of the weakest militaries on earth, Britain and France ran out of precision munitions within weeks and required urgent American resupply. Even after decades of NATO exercises on interoperability, our weapons did not fit French aircraft. That was a small campaign. Today we are being challenged by a nuclear armed state that is threatening the cables and pipelines that keep our lights on while we debate whether we might do slightly better by 2030.

Britain now faces a choice. We can rebuild our forces. We can strengthen our intelligence power. We can reindustrialise our defence base. We can fund our own strategy and shape the future of Europe. Or we can continue making promises about 2030 and pretend that numbers written in a future Chancellor’s budget amount to national strategy.

If we do not pay, we will not be heard. We can complain that the United States is making decisions without us, or we can earn our seat at the table. We cannot offshore the cost of freedom and onshore the right to shape it.

The first war of conquest in Europe since Germany and Russia invaded Poland did not emerge from an empty sky. It followed abductions in Estonia, invasions in Georgia and Crimea and years of cyberattacks and corruption directed outward from Moscow. The warnings were there. We simply chose not to look.

We are not serious people. But we could be.