Take a chance on me

How the government has strangled business by putting small firms at risk if they make one bad hire

Dutch coffee shops have always had a reputation for wacky ideas. In the 17th century, they weren’t just full of smoke, but ambition and imagination.

Adventurers, financiers, and merchants met to exchange stories and seek fortunes; they plotted voyages that would stretch across the world, to the East Indies, to Africa, to the Americas; and to plot a revolution not only in trade but in trust.

Their insight was simple but essential: no one person could carry all the risk. Sending a ship halfway around the globe was an act of faith as much as of enterprise. Storms, pirates, disease or politics could destroy months or years of investment overnight. Yet these early traders realised that if they shared the danger they could also share the reward.

By underwriting voyages and dividing ownership into shares, they parcelled uncertainty into a commodity. They fathered the first joint-stock companies and, soon after, the modern insurance markets in Amsterdam, and then in London, where the most famous coffeehouse was run by Mr Lloyd.

From that modest beginning grew one of the greatest engines of commerce the world had ever known. The idea of collective risk-taking made possible the global trade in spices, silks, and later the entire edifice of modern enterprise. It was not merely an economic innovation but a moral one, an acknowledgement that progress depends on trust: trust that others will shoulder their part of the burden, that no one will be ruined alone.

Sharing risk is the foundation for modern enterprise.

The Government has forgotten that lesson. The new Employment Bill going through Parliament does precisely the opposite. Instead of sharing risk, it heaps it onto the smallest shoulders. It tells small businesses and individual employers: you carry the uncertainty, the compliance, the penalties. And then it wonders why people stop hiring.

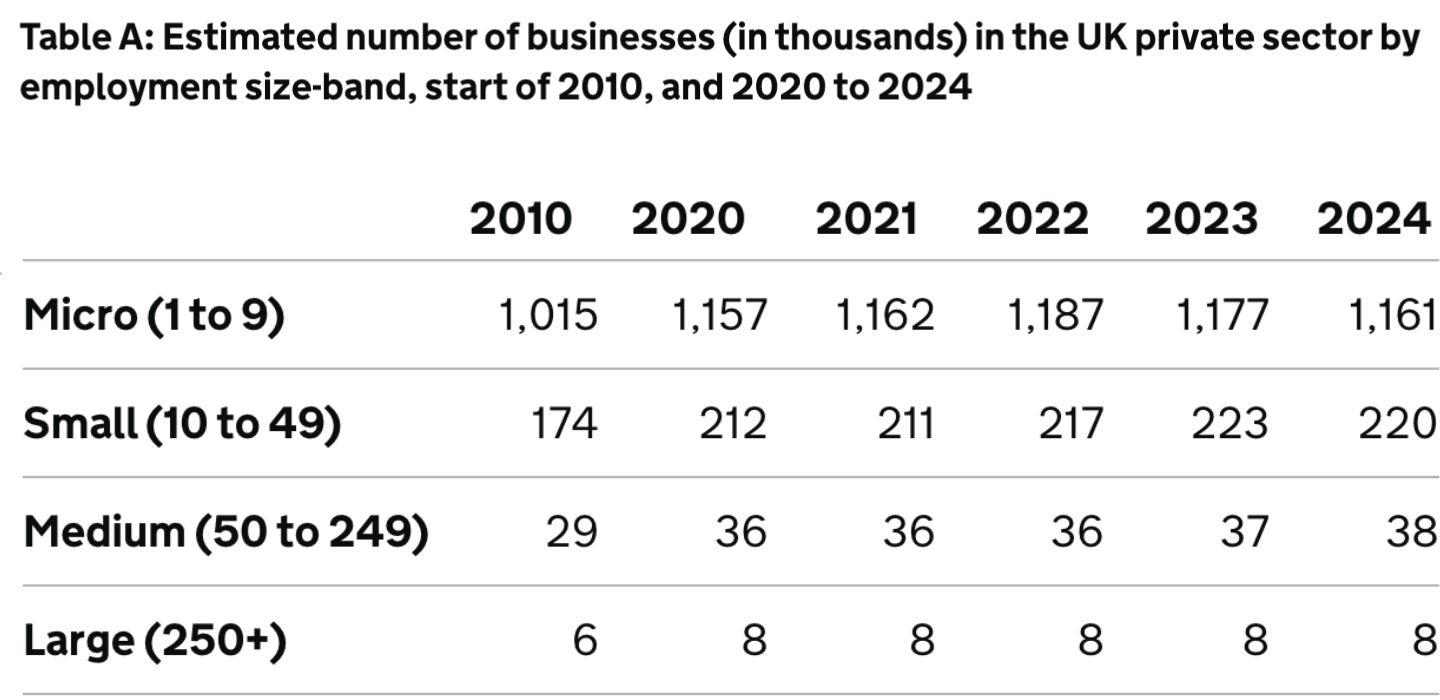

According to the Office for National Statistics, more than 80 percent of all employer businesses in the UK have fewer than ten employees. Hairdressers and builders, digital start-ups and, yes, coffee shops – they form the living tissue of our economy.

Each was built by someone who decided to take a chance, to hire, to train, to create. Every employee is a risk when a single bad hire can make the difference between profit and loss, survival and failure.

Add to that the creeping dread that any disagreement or procedural misstep could spiral into costly legal action. That each new regulation carries another layer of paperwork, another chance to fall foul of an ever-expanding rulebook.

In that environment, risk stops being something shared between state, employee and employee; it becomes a trap for those who dare to take the initiative. The safest course is to do nothing, to keep the team small, the contracts temporary, the ambition modest, and growth slow.

For those without a standard CV it’s worse. Dropped out of school? Worked abroad? Served time, or served in the Armed Forces? Why risk it? It’s like being given the rights of marriage after a first date.

Instead, the Government seeks to blame. Instead of building trust, it builds compliance. It measures, audits and fines, and is then surprised that small firms retreat and stall. This isn’t about protecting workers; many potential workers will never be hired at all, so it’s not about fairness either. It’s the bureaucrat’s idea of equality: choosing to protect those already in jobs equally and forgetting what happens to those without.

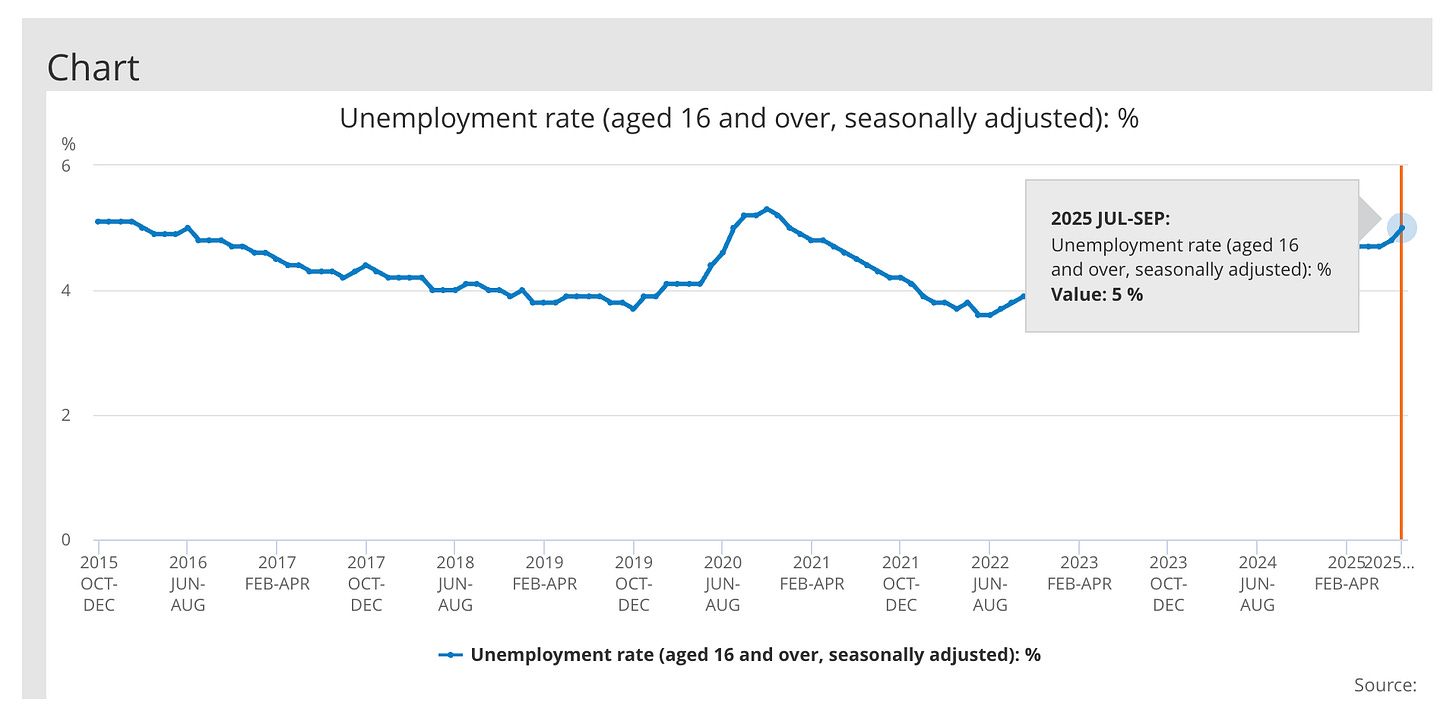

We’re already seeing the consequences. This week, the unemployment rate hit five per cent; excluding the pandemic. This is the highest in a decade and it is rising. Treating employers as though they’re all civil servants is killing enterprise.

This has inverted the logic that once made Britain great. Where early capital markets spread risk to encourage initiative, modern policy concentrates risk and suppresses it. Paralysis and caution follow, as ideas wither under the weight of fear. No Treasury scheme or productivity drive will fix that until the underlying principle is restored: trust, not control, is the engine of growth.

To rebuild trust, ministers must start by recognising that business isn’t the problem; it’s the solution. Only by sharing risk, between firms, workers, and the state, will employers have confidence that the law will be applied fairly. Simplify compliance. Streamline dispute resolution. And above all, stop legislating as if every employer were a multinational with a legal team on standby.

Britain wasn’t built in boardrooms but in backrooms, workshops, and high-street counters, by people who risk their own savings to employ others, who turn ideas into jobs, who take on people they don’t know and give them a chance. When those people lose faith that the system will treat them fairly, they stop taking risks, and we will all pay the price.

The 17th-century traders understood that prosperity is a collective act. It depends on institutions to distribute risk, laws that balance responsibility, and a government that trusts its citizens to act in good faith. Shared risk unlocks potential; concentrated risk kills it.

Ministers should go back to the coffeehouses where capitalism began. Our success wasn’t born from bureaucracy but from freedom. When we share the risk again, we will rediscover what those merchants knew: that shared burdens make greater risks and greater rewards possible.

First published in The Telegraph on the 13th of November 2025

Excellent Tom, great writing and the use of the description of the early merchants in their coffee houses was helpful/insightful. Thanks, necessary reading for Labour cabinet members and trade unionists...

Wow! Tom brought the insight from the 17C coffeehouse! Thanks for good reading always!😊🌷