The Two Empires of AI

AI may feel universal but the capability is sovereign and the power sits in the US and China. Sovereignty matters. Written together with Christopher Ahlberg.

The end of Nicolás Maduro’s rule in Venezuela along with U.S. threats to Iran shows we are in a new imperial age. This time, it isn’t only about armies, it’s about data. Artificial intelligence is revising our concepts of sovereignty and power, adding an important realm in which two nations dominate: the U.S. and China. The story is still being written, but power is concentrating in these two poles.

Sovereignty here doesn’t mean access to powerful tools or building applications on top of them. It means the ability to design, train, operate, secure and deploy foundational AI systems capable of highly advanced functions in national defence and other sensitive areas of the state without external permission or dependence. By that definition, the field already looks far narrower than most policy debates assume.

Look how the global environment has changed. For roughly 35 years after the Cold War, globalisation favoured efficiency. Supply chains linked across continents. Manufacturing migrated to lower costs. Capital and talent flowed freely. States accepted dependence in exchange for market access. The internet connected markets, narratives and politics.

That era began to unwind in the early 2020s. The pandemic exposed the fragility of supply chains, borders closed, and governments rediscovered sovereignty under pressure. What began as diversification hardened into localisation. Migration slowed across the U.S. and Europe. Security displaced efficiency as the organising principle of economic policy.

Geopolitics followed. China accelerated its bid for primacy. Russia chose war and severed itself from Europe. Across the Middle East, South Asia and the Pacific, integration gave way to rivalry, and dependence became a liability.

Yet even as globalisation reversed, connectivity didn’t. Space-based networks extended internet access. Data, content and influence continued to move across borders. The result is a world that is simultaneously deglobalising and hyperconnected. In this strange new environment, modern AI emerged.

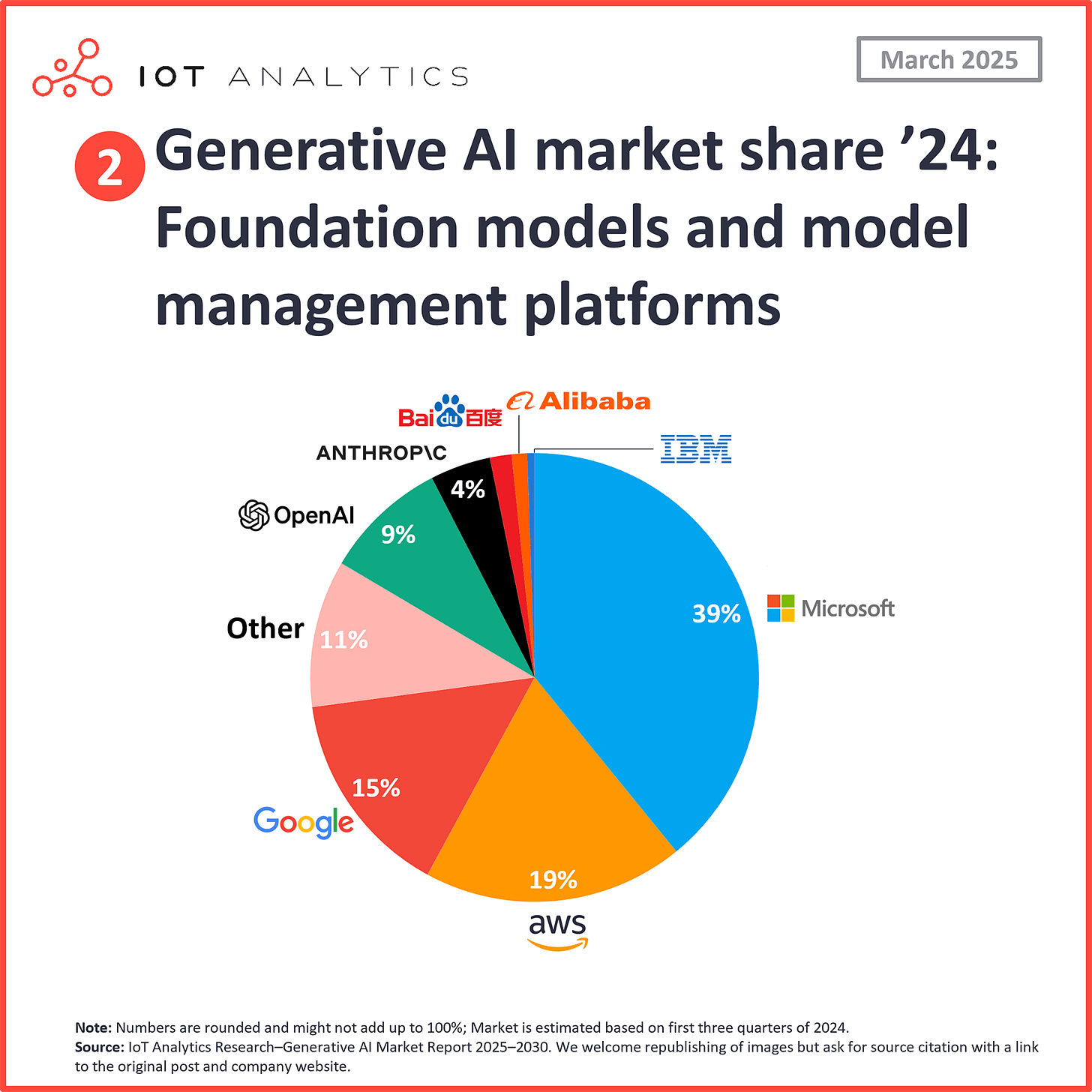

As frontier models, the technology capable of large-scale problem-solving, became widely available starting in 2022 as ChatGPT, adoption occurred at an unprecedented pace. Within months, billions of people had access to these powerful cognitive tools. Control over the underlying systems, however, concentrated into the hands of a few firms in the U.S., with China as the only rival ecosystem.

This concentration reflects three hard requirements of AI sovereignty.

First, elite competence. Not mass digital literacy, but a very small pool of people capable of building, training and operating large-scale frontier AI models. This talent is scarce, globally mobile and increasingly clustered.

Second, energy at scale. AI is power-intensive. Training and operating frontier models requires vast quantities of reliable electricity. This is a physical constraint, not a regulatory one.

Third, financial depth. Frontier AI demands sustained investment over long time horizons, often without near-term returns. Only systems with extraordinary amounts of capital can absorb that cost.

At present, only the U.S. and China appear to have all three at the necessary scale and under sovereign control.

A few countries have some of what AI sovereignty requires. The Gulf states have capital and energy but lack elite AI competence. The U.K. has exceptional talent but lacks energy scale and sufficient financial depth, as shown by the sale of DeepMind to Google in 2014.

Britain can claim DeepMind as a national success, proof that British universities and culture can produce world-class AI talent. But that talent now serves U.S. strategic priorities, operates under U.S. corporate governance, and would be subject to U.S. export controls in a crisis. The building is in King’s Cross. The sovereignty is in Mountain View.

Continental Europe should possess all three requirements but has struggled to retain its best people, many of whom now work for American-owned firms. Russia is perhaps in the worst position: It has energy, but elite competence and capital are fleeing.

There is also a fourth, less-discussed constraint. AI isn’t merely built; it must be trusted. As AI becomes embedded in the military, intelligence and cyber programs of the state, dependence on foreign systems becomes harder to justify. So autonomy is yet another requirement of AI sovereignty.

For countries outside the U.S. and China, this doesn’t mean the race is over, but it is narrowing. Some will align closely with one of the leaders. Others will seek partnerships to secure influence at the margins. Few will be able to sustain the fiction of full independence.

AI sovereignty isn’t a prize many nations can win. The strategic task then is to determine how to retain agency when technological power is concentrating rather than dispersing.

I don’t trust the Chinese they are so corrupt